NASA Captures Spooky Photo of the Moon’s Shadow on Earth During an Eclipse Leave a comment

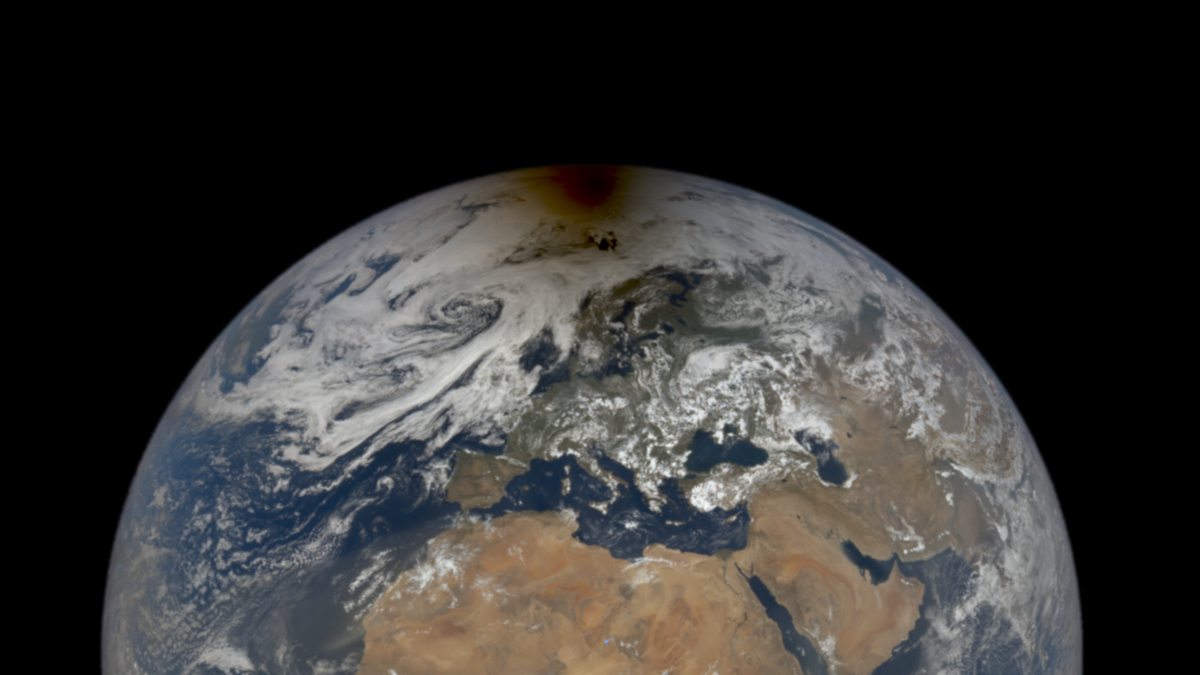

Earthlings were privy to an exciting astronomical event last month: an annular solar eclipse, which cast a lunar shadow across the Arctic Circle. Today NASA shared an image of that shadow, taken by the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) aboard NOAA’s Deep Space Climate Observatory nearly a million miles from Earth.

Since the Moon is much closer to Earth than EPIC, our lunar partner occasionally hops into pictures EPIC is trying to capture of Earth, and eclipse shadows also come with that territory. “Taking images of the sunlit half of Earth from a distance four times further than the Moon’s orbit never ceases to provide surprises, like occasionally the Moon getting in our field of view, or the Moon casting shadow on Earth,” said Adam Szabo, the project scientist on the DSCOVR team, in a NASA release. Launched in 2015, EPIC (aboard DSCOVR) has now imaged several eclipse shadows across Earth’s face: the annular eclipse last month joins total eclipse events in the 2016 and 2017 as being captured by EPIC.

Annular solar eclipses happen when the Moon moves between Earth and the Sun, causing the star to appear as a fiery halo around the Moon’s black silhouette. The recent eclipse on June 10 was partially visible to people in parts of the United States, Asia, Europe, and the Caribbean. Lucky folks in parts of Canada, Russia, and Greenland could bask in the shadow of the “ring of fire” annular solar eclipse. But no one on Earth had EPIC’s view, which captured the black-brown antumbra of the Moon camping on our planet’s North Pole. The Moon’s shadow looks like a bit of mold spreading on a fruit. Or, as one Gizmodo editor exclaimed upon viewing the image: “EARTH IS HAUNTED.”

EPIC normally images the Earth to study its climate—to give researchers on Earth a constant stream of information about the planet’s cloud cover, vegetation, and ozone. It recently captured images of the West Coast wildfires, visible even at EPIC’s distance. The satellite (DSCOVR) that hosts the camera sits at a point of gravitational balance between the Sun and Earth, called the L1 Lagrange Point. (It’s one of five such points; when it launches, the James Webb Space Telescope is headed for L2.)

G/O Media may get a commission

While total solar eclipses blot out the Sun completely, annular solar eclipses leave that solar halo around the Moon, creating an arguably cooler picture for viewers on Earth. This happens because the Moon is more distant from Earth during an annular solar eclipse, making it too small in our field of view to fully cover the Sun.

If you missed this annular eclipse, not to worry. If you’re in the Western Hemisphere, you could see another one in 2023.